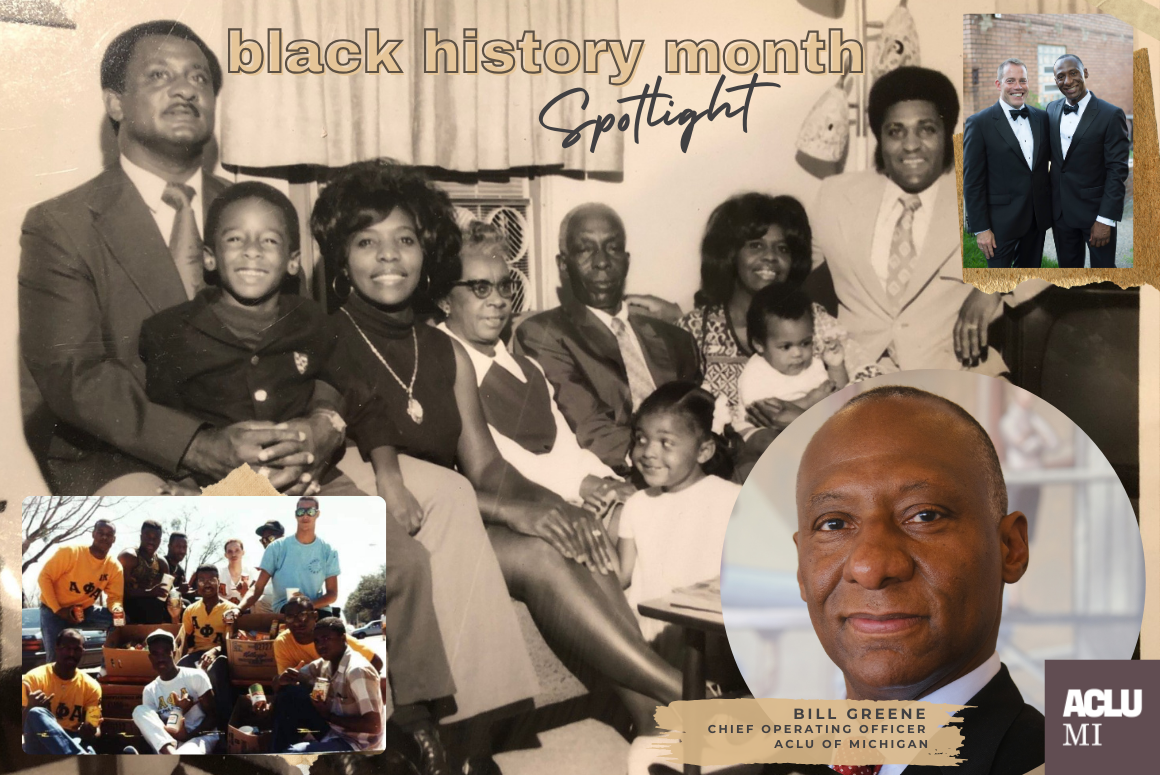

As part of our Black History Month celebration, we reached out to do a Q&A with Bill Greene who, to the surprise of no one who knows him, easily made a transition from the private sector, where he was an auto company executive and business owner, to the nonprofit ACLU of Michigan, where he is our chief operating officer, keeping a close eye on the financial side of our statewide organization.

We start by asking him, when it comes to race, how he prefers to identify, and why.

Q: Do you prefer the term Black, African American, or something else?

A: I prefer Black. In part, that’s because of the activism that was occurring as I was coming of age, and the preference for using Black among the people pushing for much-needed social change. Also, when I was older, I had a white friend who was a naturalized American citizen originally from South Africa. When he asked, “Am I an African American?” I thought the answer had to be yes. So that shaped my thinking as well. Not all Black people living in America are from either here or Africa. There are Black people from the Caribbean, from South America, Central America. We are all part of the Black diaspora.

Q: What were things like for you growing up in Louisiana during the 1970s?

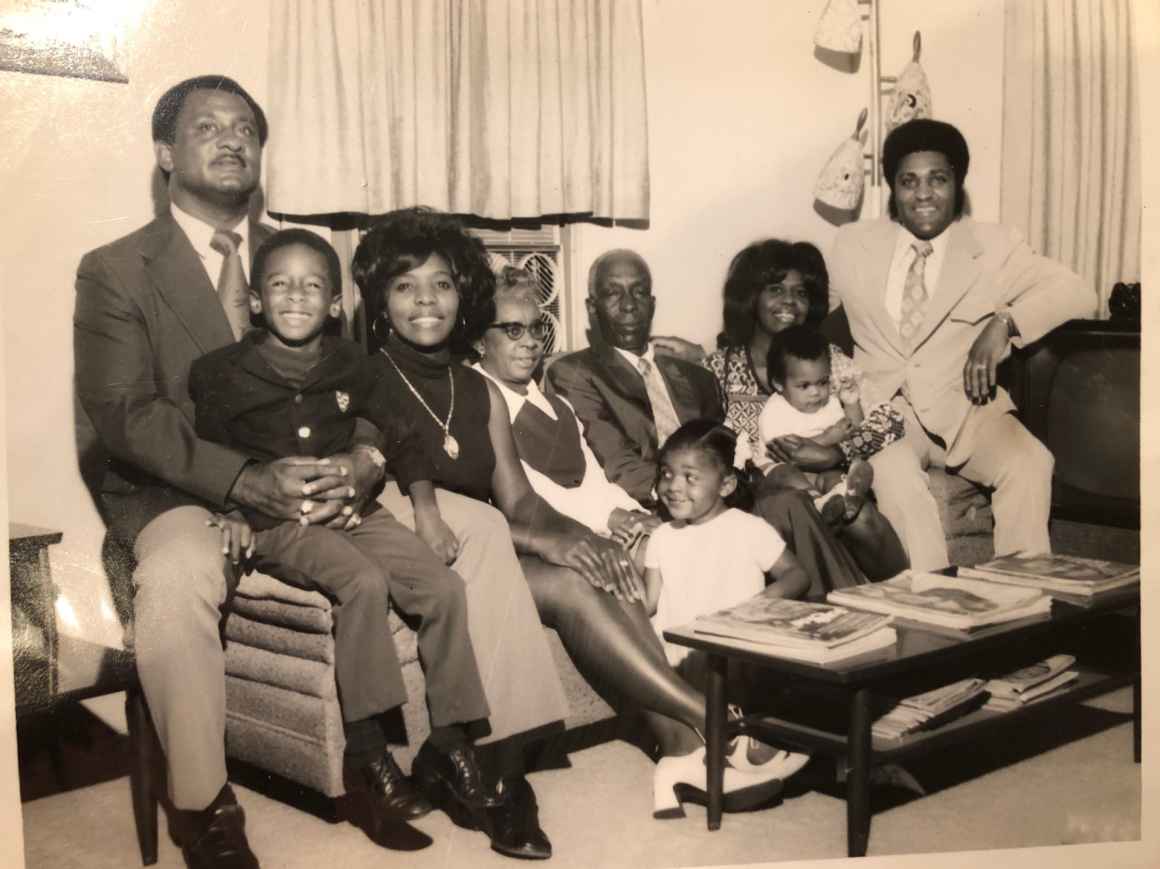

A: Racism was very prevalent at that time. As just one example, when my mother was a teenager, she worked in a restaurant that wouldn’t serve Black people. Another example was my father – who was a highly respected educator. He was passed over for an important job that went instead to a less-qualified white man. So, I was definitely aware of the racism that existed.

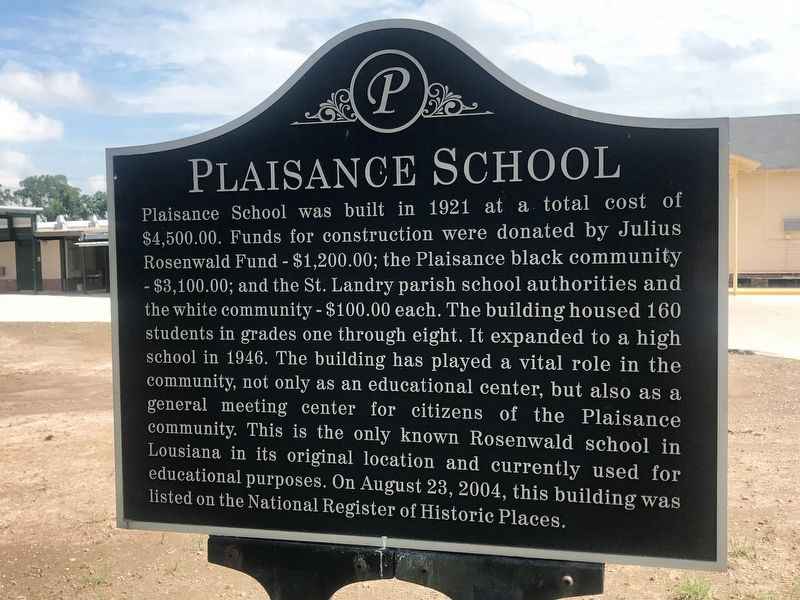

But I was very fortunate in that I grew up in an all-Black neighborhood in Plaisance, an unincorporated town near Opelousas, where a number of Black professionals started building homes for Black people to live in at a time when they were being redlined elsewhere. I was incredibly lucky to have grown up surrounded by so many positive role models in a community where people all helped and supported each other. Looking back, I can really appreciate now how important those things are.

I was also very fortunate to have grown up in a family that placed an extremely high value on education. My mother, father, and all their siblings had college degrees. One of my grandfathers was a Baptist minister, so religion also played a central role in our lives.

As a result of all that, I grew up believing there was nothing I couldn’t accomplish.

Q: How old were you when you came out as being gay?

A: I was 27, even though I knew I was gay for as far back as I remember – from the time I first became self-aware. But it was not a big factor in how I lived my life. I was captain of my football team. I was prom king. I didn’t feel like I was closeting myself. It was just that I never felt a strong need to date anyone, or to have a romantic relationship.

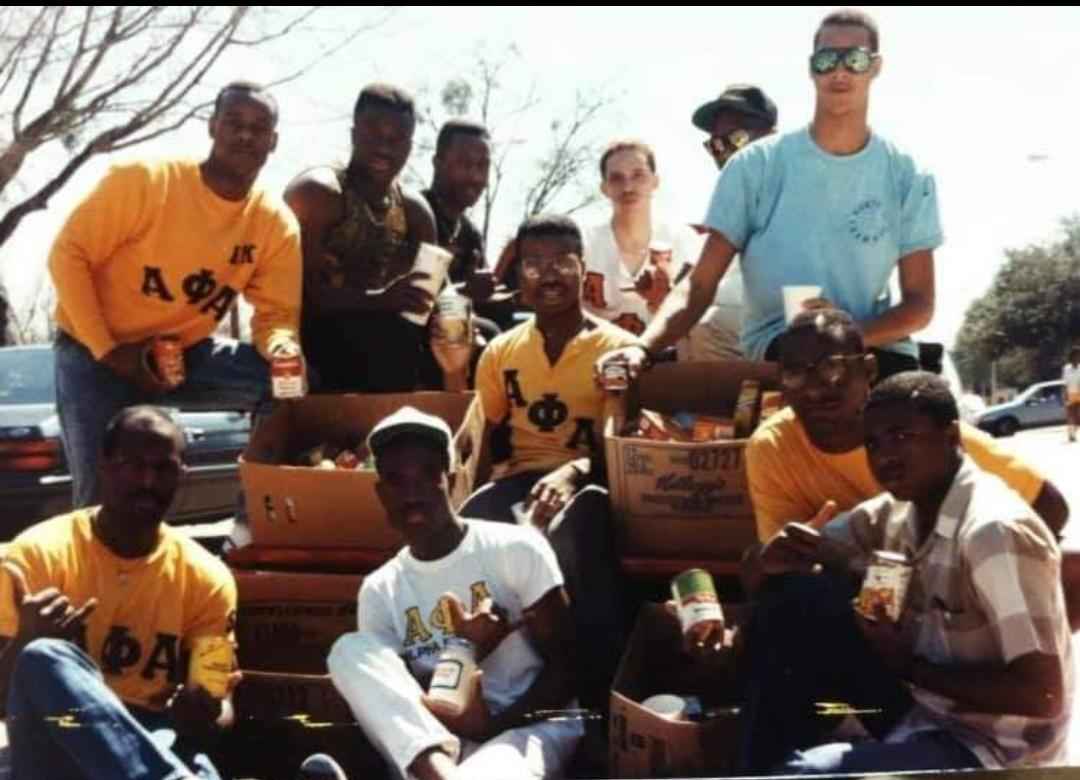

It was the same when I went away to college. I had my books. I had sports, especially tennis. And I had my church. I was content with that.

Q: What changed?

A: The person who is now my partner asked me out on a date. And I thought that, if I was going to be in a same-sex relationship, that it was important for me to come out, so that no one would think I was hiding anything. The first people I told were my brother and my mother. Both said they were not surprised at all, that they both always thought I was gay.

A: Religion has always been, and continues to be, very important to me. And it can be very painful to be rejected by people in a church because you belong to the LGBTQ+ community. I still hear some Black pastors – and, to be fair, many white conservative religious leaders – preaching intolerance.

Q: How did you reconcile issues with the church?

A: I found a church that was more accepting of people like me, and moved on. But I can also say, on a positive note, that I noticed a real change in attitude among a lot of Black churchgoers after Barack Obama became president. His open embrace of the LGBTQ + community, I think that opened a lot of eyes, and hearts.

Q: Many of us on staff have noticed that when we go out with you either for a work event or dinner, you always run into people who know you, and greet you with enthusiasm. You seem to know everyone! What do you attribute that to?

A: My father. He was a very outgoing person. He also taught me an extremely valuable lesson, which is that it is important to treat everyone exactly the same, whether it is an executive heading a massive corporation or the person who sweeps the floors at night. Whoever it is, they respond to being treated with respect, and really appreciate it when someone takes a real interest in who they are as a person.

Q: Along with working at non-profits, you have a lot of experience in the corporate world as well, both with Ford, and as the owner of a consulting business you started. What is the difference?

A: Corporations exist to maximize profits for shareholders. That’s the bottom line. But at a nonprofit organization like the ACLU, I think of the people and communities we serve as our shareholders. Instead of increased profits, we exist to help improve their lives, and the communities they live in.

Q: Is there any work the organization has done that stands out for you?

A: I think all the work we do is extremely important. From our work reforming the criminal legal system – including our groundbreaking work to address the problems caused by cash bail – to years of work protecting and expanding the rights of LGBTQ+ people, we’ve been able to accomplish so much.

But there are a couple of issues that really stand out to me as having made a really significant impact. One is the work we did in Flint around the water crisis there. We played a pivotal role in bringing that problem to light, then filed lawsuits that resulted in the replacement of all the lead water lines in the city of nearly 100,000 people. Another lawsuit resulted in the provision of much-needed special education resources for the children harmed by exposure to lead that was in their water.

A while back, I was at a grocery store in Detroit when an older Black man approached and asked, “Young man, what do you do for a living?” When I shared that I worked for the ACLU, he said: “Is it OK if I hug you? You are doing God’s work in Flint.” His gratitude really touched me. You don’t get that kind of appreciation and satisfaction in the private sector.

Another case that had a major impact involved Detroit homeowners, who were losing their homes in massive numbers as a result of their inability to pay taxes that should have never been assessed in the first place. Thousands of families were able to regain ownership and stay in their homes as a result of the lawsuit we filed.

It is very fulfilling to be a part of an organization that can have such a positive impact on the lives of so many people all across Michigan.

Q: I’d say it is safe to say, though, that our organization isn’t necessarily loved universally…

A: (laughing) Yeah, that is definitely true. I had an ACLU T-shirt on once and a guy looked right at me and said, "You assholes are destroying our country!" But it is easy to shrug off that kind of unfounded criticism. The point of our work is that it’s always important, and it is deeply appreciated by those who feel their voices are marginalized.

Q: Do you have any books you would recommend people read during Black History Month?

A: Yes. Chains and Images of Psychological Slavery, a 1984 book by clinical psychologist Naʾim Akbar. It was given to me by a friend, a nephew of Louis Farrakhan, while we were both students at Grambling. It really brought to light all the racist images, and the daily depictions of structural racism that exist, and the psychological toll it takes on Black people, and how to break free of that.

Q: What music is in heavy rotation on your playlist these days?

A: I’m a big fan of female jazz vocalists. I listen to Sarah Vaughan a lot, and Nina Simone, who I greatly admire, not just for her immense talent but also, beginning in the 1960s, how she used her music and her stature to fight for civil rights. But I’m mostly all over the place with my music. For example, I really like Buffalo Springfield, and that style of folk-rock David Crosby, Neil Young and others began making in the 1960s.

Q: Do you have a motto or favorite saying?

A: When I’m asked that, I usually think of the phrase, “Always look on the bright side of life.” But the important context is that, for me, those words are indelibly linked to a scene from Monty Python’s The Life of Brian, where the title character attaches that phrase to a cheerful tune he sings while being crucified. It’s kind of twisted, but that’s my sense of humor.